UK wealth migration: relocation patterns of billionaires and HNWIs in 2025

13 February, 2026We analysed official UK government data and international regulatory reports to understand how recent fiscal reforms are driving the relocation of wealthy individuals from the United Kingdom. The goal was to identify the key causes, preferred destinations, and long-term implications for global wealth management.

The research addresses three main questions: what factors are prompting high-net-worth individuals to leave the UK, which jurisdictions are attracting them, and how these shifts are reshaping the international residence and citizenship landscape.

The study relies on verified data from HMRC, the Office for National Statistics, and international financial oversight bodies, ensuring that all findings reflect the most recent and reliable information available as of 2025. The analysis centres on the causal relationship between major UK tax policy reforms and the outflow of wealthy residents.

Executive summary

The UK’s wealth management landscape is changing rapidly, catalysed by the most significant tax reforms in a generation[1][2][3]. The government’s decision to abolish the long-standing non-UK domiciled, or “non-dom” tax regime, effective April 6th, 2025, is the primary driver of a potential exodus of HNWIs[1][2][3].

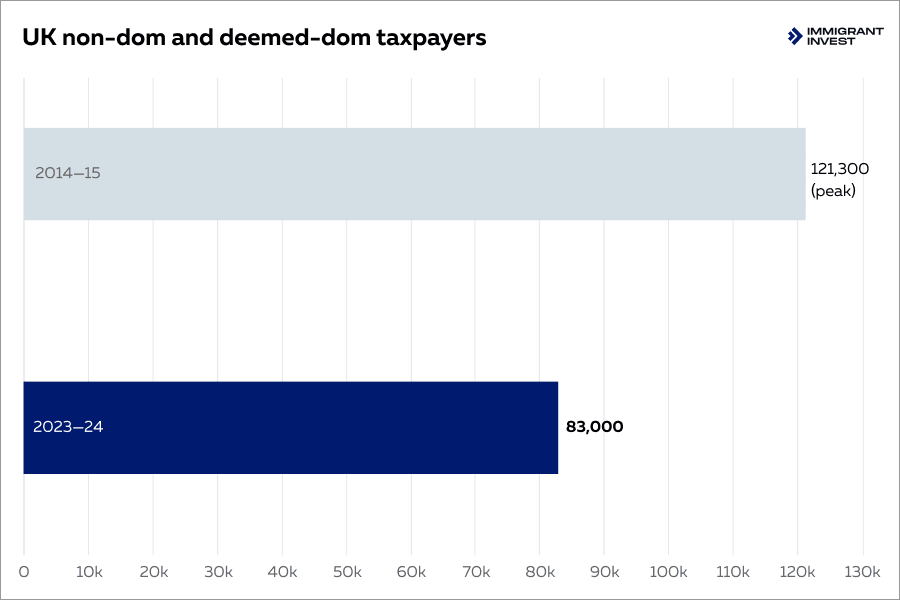

Non-dom taxpayers are already in decline. While official statistics do not segment migrants by wealth, proxy indicators point to a notable trend. The number of non-domiciled taxpayers stood at an estimated 73,700 in the tax year ending 2024, having already declined slightly before the reforms took effect[4].

Overall long-term emigration from the UK rose by 11%, reaching a provisional 517,000 in the year ending December 2024[5]. Although this includes various migrant groups, it reflects growing outflow pressure.

Tax policy changes are the main push factors. The key trigger is the end of the remittance basis of taxation. It will be replaced by a four-year regime for new arrivals and standard worldwide taxation for long-term residents[1][2][3]. This is compounded by a planned overhaul of Inheritance Tax, or IHT, which will move from a domicile-based system to one based on UK residency length[2][3].

The changes aim to increase tax “fairness” but are seen by many HNWIs as a significant erosion of the UK’s fiscal appeal[2]. Secondary triggers include the closure of the Tier 1 Investor Visa in February 2022 and increasing transparency requirements[6].

For investors and family offices, the immediate implication is the urgent need to re-evaluate UK residency status and global asset structures. Transitional provisions, such as a temporary 12% tax rate for repatriating historical foreign income and gains, offer a short window for restructuring. But the overall trend is relocation for many long-term residents.

The UK “push” is creating a strong “pull” towards jurisdictions offering greater fiscal stability and investor-friendly incentives, fundamentally reshaping the competitive landscape for residence and citizenship providers globally.

UK wealth exodus as a market event

The outflow of wealth from the United Kingdom represents a structural, market-defining event, marking a fundamental pivot away from its historical position as a haven for internationally mobile capital. This is not a temporary spike but the culmination of a long-term trend evident from 2014 to 2025.

The said structural shift is situated within a wider geopolitical context of tightening tax and compliance standards. Initiatives from the OECD, such as the Common Reporting Standard and the development of the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework, have systematically eroded global banking secrecy[8].

Official HMRC statistics show a significant decline in the non-domiciled taxpayer population from a peak of 121,300 in the 2014/15 tax year to a combined non-dom and deemed-dom population of approximately 83,000 in the tax year ending 2024[7]. This precedes the final abolition of the regime in 2025, indicating a sustained erosion of the UK’s attractiveness over the last decade

Concurrently, the European Union’s new Anti-Money Laundering package, featuring a single rulebook and a new supervisory authority, AMLA, creates a more stringent and harmonised regulatory environment across the bloc[9].

The UK’s policy changes, framed around “fairness” and modernisation, align with this global trend[2]. This creates a powerful “push-pull” dynamic. The UK is exerting a significant “push” through regulatory and fiscal pressure, most notably the abolition of the non-dom regime and the move to a residence-based Inheritance Tax system[2][3].

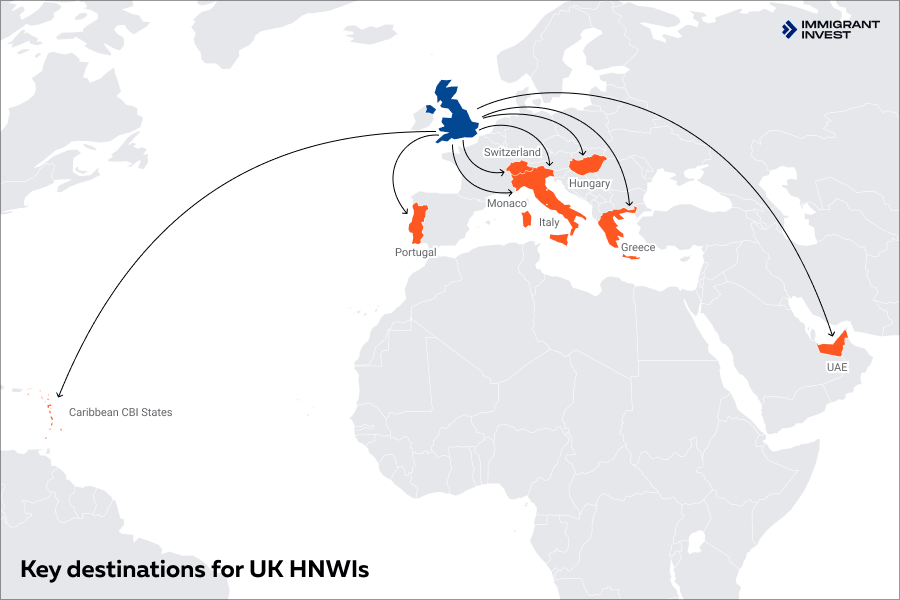

The policy-driven push is met by the strong fiscal “pull” of low-tax jurisdictions. Countries like the UAE and Monaco offer zero personal income tax, while others like Italy and Greece have implemented attractive flat-tax regimes for new residents[10][11].

Robert Outerbridge,

Investment Migration Expert

The UK’s deliberate dismantling of its primary fiscal incentive for HNWIs, combined with the magnetic appeal of these competing hubs, has redefined the market for wealth migration, turning a gradual trend into a decisive structural event.

Destination landscape and segmentation

Destinations drawing interest from UK-based high-net-worth individuals fall into three strategic clusters, based on investor motivation.

Strategic clusters for UK-based HNWIs

This segmentation highlights a clear divergence in strategy. Tax optimisation hubs compete on the simplicity of a near-zero tax burden. EU options offer a package of lifestyle, mobility within the bloc, and predictable, favourable tax regimes for a defined period. The Caribbean states offer a different value proposition entirely: a portable identity asset in the form of a second passport

Tax optimisation hubs

These jurisdictions are chosen for their highly favourable tax environments. They typically offer:

- zero or very low personal income tax;

- no capital gains tax;

- no wealth tax.

The main motivation is fiscal efficiency and long-term wealth preservation.

EU relocation options

The group includes European Union member states offering:

- EU residency rights, including freedom of movement and establishment;

- residence by investment programmes;

- special tax regimes for new residents.

Investors in this cluster seek a mix of lifestyle benefits, EU access, and tax advantages. However, tax authorities are paying closer attention to where someone’s real life is based: time spent in each country, day counts, and practical ties — home, family, work — not just whether they hold a residence permit.

Global mobility and asset protection plays

The cluster consists of countries offering citizenship by investment programmes. These destinations attract investors aiming to:

- obtain a second passport for visa-free travel;

- diversify their citizenship portfolio as a hedge against geopolitical risk;

- support international business and banking strategies.

Regulatory and fiscal architecture of key destinations

The attractiveness of each destination cluster is defined by its specific regulatory and fiscal architecture.

For HNWIs leaving the UK, the decision is a complex calculation involving residency requirements, tax liabilities, and the long-term compliance environment.

Comparative fiscal architecture of key HNWI destinations

The table reveals a clear trade-off. The UAE and Monaco offer the simplest and most compelling proposition on headline tax rates, but EU destinations provide the significant benefit of freedom of movement and establishment within the bloc. Switzerland offers a unique, negotiated tax status but with the complexity of cantonal variation and a wealth tax. The Caribbean states provide an entirely different product focused on global mobility and asset diversification through a second citizenship

UK policy shifts and behavioural triggers

A series of deliberate UK policy shifts have acted as powerful behavioural triggers for wealth migration, culminating in the landmark reforms of 2025[3][24].

The most significant trigger is the government’s announcement in the Spring Budget 2024 to abolish the remittance basis of taxation for non-UK domiciled individuals from April 6th, 2025[24]. This policy replaces the centuries-old regime with a new, time-limited four-year Foreign Income and Gains regime for new arrivals, after which they face tax on their worldwide income[3].

The announcement created a one-year lag, prompting a wave of strategic planning and restructuring among the affected population. This primary trigger was reinforced by the simultaneous announcement of plans to move Inheritance Tax to a residence-based system, subjecting long-term residents to IHT on their worldwide assets after 10 years of UK residence[3].

In UK estate planning, trusts set up before April 2025 are increasingly treated as a firm legal boundary with different outcomes, rather than something that can be adjusted freely later.

Major reforms were preceded by significant secondary triggers. The closure of the Tier 1 Investor Visa route in February 2022 abruptly cut off the main immigration pathway for passive investors, signalling a shift in the UK’s attitude towards attracting capital[6]. Furthermore, the implementation of the Register of Overseas Entities in August 2022, which mandated the disclosure of beneficial owners of UK property, increased the compliance burden and reduced privacy[26].

An earlier, foundational trigger was the April 2017 implementation of “deemed domicile” rules, which ended permanent non-dom status for long-term residents — 15 of the last 20 years — and was immediately followed by a sharp reclassification and a drop in non-dom numbers in HMRC’s official statistics[27][28].

The combined effect of these policies has been to progressively dismantle the fiscal and legal framework that made the UK attractive to internationally mobile HNWIs, directly triggering the observed and anticipated outflows.

Compliance, risks, and opportunity environment

The global landscape for private wealth is being reshaped by a synchronised tightening of compliance and transparency standards, creating both risks and opportunities for migrating HNWIs and the advisors who serve them. International bodies are creating a more stringent and uniform regulatory environment.

Financial Action Task Force — FATF

As of late 2025, the FATF compliance landscape shows significant variation. A major development is the placement of Monaco on the FATF’s “grey list” in June 2024, which means it is under increased monitoring to address deficiencies in its anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing regime[29].

Conversely, the UAE was removed from the same list in February 2024 after making substantial progress[30]. Key jurisdictions like Switzerland, Italy, Portugal, Greece, Hungary, and the main Caribbean CBI states are not on the FATF’s public “grey” or “black” lists[31].

EU Anti-Money Laundering Package

In 2024, the EU finalised a landmark AML package, establishing a single, directly applicable rulebook across the Union and a new Frankfurt-based supervisory body, the Authority for Anti-Money Laundering [9][32].

As the new Anti-Money Laundering Authority starts operating, enforcement standards across EU countries are becoming more consistent. That makes “easier” EU jurisdictions less useful for anyone hoping for a lighter compliance approach.

OECD Tax Transparency

The OECD’s Common Reporting Standard has effectively ended banking secrecy for tax purposes, and the upcoming Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework will extend this transparency to digital assets[8].

Data limitations and strategic opportunities

The tightening compliance environment creates both challenges and opportunities. The significant data gap between the acquisition of a new residence permit and the formal relocation of one’s tax domicile remains a key challenge for analysis.

Official statistics on the final destinations of UK emigrants are not readily available, making it difficult to quantify flows accurately and forcing a reliance on proxy data[33].

However, the environment also creates opportunities. The rising competition among low-tax hubs to attract capital and talent is leading to the creation of new and refined incentive programmes.

Robert Outerbridge,

Investment Migration Expert

For investment migration providers, this is a chance to move beyond simple programme sales and reposition as indispensable strategic advisors, guiding clients through a complex, multi-jurisdictional landscape of risk and opportunity.

We already do it at Immigrant Invest: before we offer any solution, we carefully study the client’s case.

Strategic implications for market players

The structural changes in the UK’s tax landscape demand a fundamental repositioning for market players serving HNWIs. Success now depends on moving from a transactional sales model to a long-term, strategic advisory role.

Positioning shift to holistic fiscal relocation strategy

The era of simply advertising a Golden Visa or citizenship programme is over[3]. The complexity of the UK’s new residence-based system, with its time-limited incentives and long-term tax consequences, requires a shift to “holistic fiscal relocation advisory.”[3]

The advisor’s role must evolve to that of a strategic project manager, guiding the client’s entire multi-year fiscal journey. This includes planning for the transition to the UK’s standard tax rules after the initial four-year FIG regime and addressing the 10-year trigger for worldwide IHT exposure[3].

In short, advisers are now building step-by-step plans that prioritise when someone stops being a UK tax resident and when they become tax resident elsewhere, instead of starting with getting a visa straight away.

Companies are stepping back from “zero-tax” claims and shifting to messaging about stable, predictable tax systems that follow clear rules, to stay aligned with advertising and consumer protection requirements.

Messaging: problem—solution framing

Messaging must be grounded in the official facts of the new UK policy to build credibility[3]. Key themes should be framed as solutions to client problems:

- Tax complexity. Solution: Frame the new 4-year FIG regime as a “clear, four-year tax holiday on all foreign income and gains for new residents,” emphasising simplicity and predictability[3].

- Succession uncertainty. Solution: Proactively address the new IHT rules by advising to “plan ahead for UK Inheritance Tax, which will apply to your worldwide assets after 10 years of residence.”[3] A crucial point is that “existing trust structures holding non-UK assets settled before April 2025 retain their IHT-protected status”[3].

- Missed opportunities. Solution: Create urgency for existing non-doms by highlighting the time-sensitive transitional rules, such as the 12% Temporary Repatriation Facility[34].

Robert Outerbridge,

Investment Migration Expert

In the short term, wealthy individuals are focusing on restructuring and using transitional measures such as the temporary 12% repatriation facility. Advisory firms report a surge in applications for EU residency and citizenship programmes during this adjustment window.

In the long term, however, the shift to a residence-based inheritance and income tax system will alter the UK’s competitive standing permanently. Over a decade, this is likely to reduce London’s dominance as a private wealth hub and strengthen emerging centres such as Dubai and Lisbon.

Methodology and sources

The foundational principle of this research is the exclusive reliance on official, replicable statistics. All data from private vendors and media-compiled lists are explicitly excluded from the analysis[35].

The primary proxy for HNWIs Individuals is the official definition used by HM Revenue & Customs for a “wealthy individual”: any individual with an income of £200,000 or more, or assets of £2 million or more, in any of the last three tax years[36].

There is no official UK government statistic or count of billionaires. Both HMRC and the National Audit Office have confirmed that UK tax legislation requires reporting on income and taxable events, not an individual’s total net worth[37]. This acknowledged data gap makes it impossible to quantify billionaire migration flows using government data.

Confidence in the data used is graded based on its official status and methodological transparency. “High Confidence” is assigned to official statistics published by primary bodies like the Office for National Statistics and HMRC that are accompanied by detailed Quality and Methodology Information reports[35]. “Medium Confidence: is assigned to official statistics with known limitations, such as provisional data[35].

Key findings

- The abolition of the UK’s non-domiciled tax status in April 2025 marks the most consequential change in decades, prompting high-net-worth individuals to reassess their tax residency and asset structures.

- Outbound UK wealth is concentrated in three strategic destinations: tax optimisation hubs such as UAE, EU relocation options, and global mobility jurisdictions through citizenship by investment.

- While zero-tax jurisdictions attract attention for simplicity, EU countries increasingly compete through predictable flat-tax regimes that combine fiscal benefits with lifestyle and freedom of movement within the bloc.

- New frameworks from the OECD and EU — including the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework and the AMLA supervisory authority — are creating a uniform transparency environment that limits arbitrage and demands more sophisticated, compliant relocation planning.

- Wealth advisors must evolve from promoting visa products to orchestrating long-term fiscal relocation strategies, guiding clients through tax transitions, inheritance planning, and multi-jurisdictional compliance across a 10-year horizon.

Sources for the analytical report

-

Source: Changes to the taxation of non-UK domiciled individuals are detailed on the official UK government website.

-

Source: Reforming the taxation of non-UK domiciled individuals is published on the official UK government website.

-

Source: The full report Reforming the taxation of non-UK domiciled individuals is available as a PDF on the UK government website.

-

Source: Data on non-dom residents and taxation reforms are covered in Bloomberg’s report.

-

Source: Long-term international migration data are available on the Office for National Statistics website.

-

Source: The closure of the Tier 1 Investor Visa route is announced on the UK government website.

-

Source: Recent developments on non-domicile taxation are discussed in the UK Parliament research briefing.

-

Source: OECD provides information on tax transparency and international co-operation.

-

Source: The EU Council adopted a package of rules on anti-money laundering, published on the Council of the European Union website.

-

Source: PwC outlines individual income tax rules in the UAE.

-

Source: The Greek Independent Authority for Public Revenue outlines tax incentives for attracting new tax residents (PDF).

-

Source: Country profile for Monaco is published on the FATF official website.

-

Source: Information on residence and relocation procedures is available on the official website of the Mission of Monaco to the United Nations.

-

Source: The structure of the Swiss tax system is detailed in the Swiss Federal Tax Administration PDF.

-

Source: PwC provides details on other individual taxes in the UAE.

-

Source: The IBR Group offers a comprehensive guide to UAE taxation in 2025.

-

Source: Contact information for the Direction des Services Fiscaux is listed on Monaco1.

-

Source: Details on Monaco’s international tax agreements are published on the official Government of Monaco website.

-

Source: OECD provides information on international tax treaties.

-

Source: PwC explains the lump-sum taxation system in Switzerland (PDF).

-

Source: Italy’s special tax regime for new residents is described on the Investor Visa for Italy portal.

-

Source: Information about Antigua and Barbuda’s citizenship by investment is available on the official CIP website.

-

Source: The UK government’s publication on tax changes for non-UK domiciled individuals outlines major reforms.

-

Source: The Spring Budget 2024 (HC 560) PDF report provides details of the UK’s fiscal policy changes.

-

Source: Guidance for registering an overseas entity and its beneficial owners is available on GOV.UK.

-

Source: Statistical commentary on non-domiciled taxpayers is available on the UK government website.

-

Source: GOV.UK provides guidance on deemed domicile rules.

-

Source: The FATF list of jurisdictions under increased monitoring (June 2025) highlights high-risk countries.

-

Source: FATF’s profile of the United Arab Emirates outlines the country’s compliance measures.

-

Source: The FATF update on jurisdictions under increased monitoring (February 2025) details newly assessed countries.

-

Source: Regulation (EU) 2024/1620 is available in English on the EUR-Lex database.

-

Source: The UK government migration statistics collection provides official migration data.

-

Source: The Finance Act 2025 PDF is available on legislation.gov.uk.

-

Source: The quality report on statistics of non-domiciled taxpayers is published on the UK government website.

-

Source: The UK National Audit Office (NAO) report Collecting the right tax from wealthy individuals (PDF) examines compliance among high-net-worth taxpayers.

-

Source: The full NAO report on collecting the right tax from wealthy individuals is available on the NAO website.